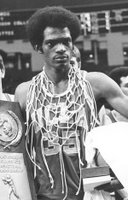

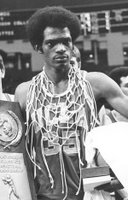

Sidney

Wicks helped UCLA to three consecutive NCAA basketball championships. in 1969, 1970, and 1971.Colleges around the nation took it for granted UCLA's basketball dynasty would end with the graduation of Lew Alcindor's in 1969. However, Sidney Wicks, Curtis Rowe, Steve Patterson, and others proved them wrong.Wicks averaged 15.8 points and 9.9 rebounds per game at UCLA. He ranks No.21 on UCLA's all-time scoring list (1423) and No.9 overall in rebounds (894).His No.35 jersey was retired by UCLA.WICKS KEEPS NBA LIFE IN PASTBy Kerry Eggers

Writer, Portland Tribune

WILMINGTON, N.C. — The water is deep blue, the air crisp and the sky clear on a Tuesday afternoon in this coastal city, a good four-hour drive from Charlotte.

Sitting in a chair on the inside deck of the Bluewater Grill, overlooking the intercoastal waters of the Atlantic, is a man old-time Trail Blazer fans will easily recall.

“But you have to be at least 35 years old to remember me,” Sidney Wicks says, smiling. “Anybody younger than that has no clue.”

It’s been 30 years since Wicks wore a Blazer uniform, 25 years since he played his final game in the NBA. The 6-9 forward out of UCLA, the No. 2 pick in the 1971 draft, put up spectacular numbers in his five years with Portland, averaging 22.3 points and 10.3 rebounds. He was rookie of the year in 1971-72 and made the All-Star Game in his first four seasons.

Yet Wicks’ reputation as a player — both in Portland and with Boston and the San Diego Clippers, for whom he finished his 10-year career in 1981 — was as somebody who never reached his vast potential. After averaging 24.5 points and 11.5 rebounds as a rookie on a Blazer team that went 18-64, his scoring average went down in each of his next nine seasons in the league.

The season after Wicks’ contract was sold to Boston, the Blazers won the NBA championship. Wicks never got as far as the NBA finals and appeared in only nine playoff games.

Many within the Portland organization at the time — front-office types, coaches and players — considered him a malcontent, an enigmatic player who had the makeup of a leader but was more out to serve himself than the group.

Wicks’ relationship with the team’s other star, Geoff Petrie, was adversarial by all accounts except, well, perhaps that of the two parties today.

After he left the NBA, Wicks played another season in Italy and spent an additional year living there. He returned to UCLA and served four years as an assistant coach under Walt Hazzard.

Over the next two decades, Wicks all but vanished.

“When I stopped coaching, I decided it was my time to have my anonymity, but also to be who I am and do what I want to do,” Wicks says. “That doesn’t make me a recluse. It just allows me be do my own thing, be my own person. It has worked out well.”

In a rare interview, he offers Portland Tribune readers a look back at his time in Portland, along with a glimpse at Sidney Wicks today.

Life is goodWicks, 56, weighs 240 pounds, maybe 10 pounds over his playing weight. He looks younger than his years and appears to be in great shape.

“I work out, and I watch my diet,” he says. “That’s the only way I can do it.”

Even on a cool day, with the temperature in the 50s, he wears khaki shorts, a polo shirt and deck shoes.

“This is me, especially during the summer,” he says. “Unless I go to Los Angeles. Even there, during the day, it’s casual. Then there’s a different dress style in the evening.”

Wicks retains a home in L.A. and is there for seven- to 10-day stretches several times a year. He has made a living in real estate investments there the past 20 years, he says, and also goes to visit friends and family members.

His daughter, Sibahn Epps, is a budding agent in Hollywood after spending five years as a writer in the music industry, he says. Epps, born during Sidney’s time in Portland, is his only child, the product of a seven-year marriage that ended in 1979.

Wicks, who is single, smiles often, speaks freely and accommodates all questions except about his current personal life.

“Just want to keep that private,” he says.

Over the last 20 years, Wicks has lived in L.A., Atlanta and Amelia Island, Fla. While in Atlanta, he began visiting the Wilmington area on vacation trips. He enjoyed it so much, he decided to settle here three years ago.

Wicks’ four-bedroom beach-style waterfront home in suburban Hampstead is a place where he can relax year-round and take his 20-foot johnboat or jet ski out in the summers. He travels often.

After his coaching stint at UCLA was over, “I started to try to figure out what I wanted to do from there,” Wicks says. “What I wanted to do was have a good quality of life. That’s what I’ve been doing.”

For a while, Wicks owned and operated six dry cleaning agencies in the San Diego area. It was during that time, about 1990, that he was involved in a serious traffic accident. His car was broadsided by a cement truck. He suffered a ruptured spleen, broken ribs and other injuries. He was unconscious for a week and remained in the hospital for three weeks.

“It was a tough time,” he says. “The doctor told me, ‘You’re going to be OK because you’re in shape. Anybody else, it might take them two to three years to recover.’ I was up and around in four or five months.”

Wicks has done few interviews since his coaching days at UCLA, but not because he won’t cooperate.

“I have spoken to the media on occasion,” he says, “but a lot of times, I’ve been living in places where most people don’t know where I am. I haven’t done an interview (for a media outlet) in the Northwest in, oh, 30 years. I’m more than willing to talk about my time in Portland. I loved it there. Portland is a great place to live.”

Wicks recalls that his home was in the Hillsdale area of Southwest Portland.

“I still have friends there I made from back then,” he says. “Not people I played with; I’m talking about neighbors and friends and acquaintances I made there.”

Asked if he keeps in touch with any of his ex-teammates from Portland, Wicks thinks.

“Not really,” he says. “I spoke with LaRue Martin maybe four, five years ago. Other than that, not really.”

An immediate impactAn L.A. native, Wicks was the guiding light on UCLA teams that won three consecutive NCAA championships and lost four games in three years under coach John Wooden.

“It was the best college experience a kid could have had,” says Wicks, who earned his degree in sociology. “Athletically, it was the best; personally and academically, it was the best situation you could have at any college. The curriculum, the campus life, the way of life there was unbelievable.”

In essence, Wicks was the No. 1 player in the 1971 draft. Portland paid Cleveland to take Austin Carr with the first pick, paving the way for the Blazers to select Wicks.

There was little question about Wicks’ talent. He led Portland in scoring in three of his five seasons. He still holds the franchise record with 27 rebounds in a game. He ranks fifth in career rebounds and ninth in scoring.

But before he played an NBA game, Blazer management questioned its own selection.

“When you talk about Sidney Wicks, it’s hard for me,” says Stu Inman, then Portland’s director of player personnel. “I would have drawn the conclusion he would have had a much better career.”

The summer of 1971, Inman says, the Blazers began a relationship with sports psychologist Bruce Ogilvie in which he would provide psychological profiles on prospects before the draft. That summer, though, he tested Portland’s picks after the draft.

“In drafting Sidney, I was going on what John Wooden and his assistant coach told me, and what I saw on the court,” Inman says. “We needed a power guy who could score, and Sidney was both. There was no question about his talent level.

“I remember I was sitting in a Lewis & Clark College lecture room with our owners (Larry Weinberg and Herman Sarkowsky) and (general manager) Harry Glickman. Bruce was unbelievably honest about the frailties in Sidney’s athletic personality. The more Bruce talked, the more the owners slumped in their chairs. Sidney didn’t fall down in just one or two categories, but four or five, which really raised the red flag. Had we known, we probably would not have taken him.”

But Wicks proved immediately he was a gifted player.

“He was the prototype of power forwards today,” says Lionel Hollins, whose rookie year with Portland was Wicks’ last season there. “He was big, could run the court, shoot, post up, pass, put the ball on the floor … he could do it all as a player, and he played hard.”

Wicks joined a Portland team led by second-year guard Petrie, who had averaged 24.8 points while earning All-Star recognition and co-rookie of the year honors. Two strong personalities clashed immediately. Through five turbulent seasons, they never really jelled, though each respected the other’s abilities.

“Sidney was a unique blend of power, speed and quickness,” Petrie says today. “He was also was a pretty good passer for a frontcourt player.”

At times, though, it appeared the court wasn’t big enough for the both of them.

“There were clearly problems between Wicks and Petrie,” says Bobby Gross, also a rookie during Wicks’ final year in Portland. “You didn’t see it so much in the practice or games, but you kind of felt it.”

“Sidney and Geoff didn’t really get along,” says Jack McCloskey, Wicks’ coach for two seasons in Portland. “I tried to get them to communicate. I don’t know why they had the problem. I’m sure they did the best they could.”

The incidentIt didn’t take long for things to come to a head. On Dec. 30, 1971, two months into Wicks’ rookie year, Portland lost 117-92 at Chicago. Wicks, who had 23 points and 14 rebounds, unloaded on the team in a post-game radio interview with Bill Schonely.

“We degenerated into a group of individuals tonight and never resembled a team,” Wicks told Schonely. “We played like it was just a pickup game in a high school gym. Guys just wandered on and off the court and never gave up the ball. Everybody out there is playing for themselves, and it stinks. Some people are playing team ball; some people aren’t. We’re out there getting the crap kicked out of us by teams we can play with. There are too many guys dribbling with their heads down and not looking for others.

“All this, coupled with the fact that everybody expected me to somehow turn this franchise around, has been very disappointing to me. A lot of people in Portland are supporting us right now, but I don’t think we warrant that support. I wouldn’t go see the Trail Blazers because we’re not playing professional basketball.”

The media took Wicks’ comments to be directed mostly at Petrie, now president of basketball operations for the Sacramento Kings. So did Petrie, who the following day was quoted as saying: “Twice (when Petrie took shots), he (Wicks) just stood there and shook his head like he should have had the ball. I ran around for six games and never saw the damn ball. Now all of a sudden, he doesn’t think he’s getting it enough? He is just as guilty as anyone else. We have all chiefs and no Indians. Something has to be done, or we won’t win another game all year.”

But Petrie agreed with Wicks that there was too much selfishness among the Blazers, “and I’ll take a lot of the blame.” He also said there was no reason he and Wicks couldn’t play together.

Wicks remembers his outburst in Chicago.

“I said we as a team were not playing well,” he says. “I included myself. I wasn’t directing it at one person, but people construed it as being toward Petrie.”

Teammates often baffled

After the 1971-72 season, Inman and his wife took Petrie, Wicks and their wives on a trip to Israel. It was the brainstorm of Weinberg, who hoped it could cement a better relationship between the two stars.

Ironically, Petrie saved Wicks’ life. The group had gone out for a swim in the Sea of Galilee when Wicks found himself in peril.

“Sidney got cramps in both of his legs and started calling for help,” Petrie says. “He wasn’t far out, and I got him to shore. He coughed up a lot of water. Finally, he said, ‘Thanks a lot. I’m too young to die.’ ”

Did it help heal their relationship?

“There was really nothing wrong with it to begin with,” Wicks says. “Of course I was appreciative that Geoff pulled me out of the water. The trip, it worked out. We got a chance to be exposed to one another in a social setting, which was really cool.”

To their teammates, however, nothing seemed to change.

Most of those on the team and within the organization agree that Wicks and Petrie share responsibility for their rift.

“They were both big names, young and selfish, and never figured it out during their time together,” Inman says. “Geoff was Geoff, and Sidney was self-destructive.”

Lenny Wilkens took over the Blazers, first as player-coach and then as coach, for Wicks’ final two seasons in Portland.

“The chemistry on the team wasn’t great,” says Wilkens, now retired and in the Hall of Fame. “When I came to that situation, one of the things they hadn’t learned to do was how to play together. The whole team needed to understand one another. We started to get it toward the end, but then they broke us up.”

Some of Wicks’ teammates resented his demeanor. Hollins recalls his first meeting with Wicks, at the doctor’s office when the players were taking preseason physicals.

“I had rooted for him at UCLA and had really been looking forward to meeting him,” Hollins says. “He was one of the last to get to the doctor’s office. We were sitting around playing cards and waiting. He came over to me and said, ‘My name is Sidney Wicks. You can call my Sidney, or you can call me Sy, but don’t call me Sid.’

“A lot of his attitude had to do with the success he had playing for John Wooden. On several occasions he mentioned there was only one really good coach in basketball, and only one really good school. He was very stat- and image-conscious. I wouldn’t say he was a great teammate. He was about Sidney Wicks, about making sure he was taken care of. Sidney got along with everybody he wanted to get along with. He’d always talk about himself in third person. But I can’t say Sidney’s a bad guy. I never really knew him.”

Besides Wicks’ admonition not to call him Sid, Gross noticed other things.

“A lot of times, Sidney wouldn’t pay close attention to what (Wilkens) was talking about,” Gross says. “Being a rookie, that flabbergasted me. He broke my nose in practice one day and seemed to be very proud of it. It bothered me that he was very proud of the fact.

“I remember Sidney was often the last one to practice and the first one to leave. And he liked to shoot at a basket by himself.”

Thirty years later, this is not the portrait Wicks paints of himself as a Blazer.

“Was I a loner? Not to my knowledge,” he says. “I’ve never been that kind of guy. I’m one of the guys who is gregarious and outgoing.

“Look, it was a difficult situation when I was in Portland. Our team was in constant turmoil, changing players and coaches.”

And, “in my early 20s, there was a lot of growing up to do.”

Moving onThe Blazers got a little better each year during Wicks’ time with the team, and his scoring average went down every season, to a team-high 19.1 points in 1975-76. His shooting percentage went up every season until the last one.

“The better quality of team you have, your average is supposed to go down some,” he says. “You don’t have to score as much.”

With second-year center Bill Walton missing 31 games due to injury in 1975-76, the Blazers went 37-45 and missed the playoffs for the sixth straight year. After the season, Portland hired Jack Ramsay as coach, acquired Maurice Lucas and Dave Twardzik in the expansion draft and got Johnny Davis in the college draft. In October, Wicks was sold to Boston. Eight months later, the Blazers reigned as NBA champions.

“Go figure,” Wicks says. “And (the Celtics) almost played them in the finals, which would have been even more ironic. We lost to Philadelphia in seven games in the East finals. But Portland added all the ingredients, including a healthy Bill Walton, and got a championship. I can honestly say God bless everyone for that.”

Wicks is remembered as a good but not great NBA player. There’s a certain sadness to that, because in a different situation he might have achieved greatness.

And chances are, the teammates who resented his comportment 30 years ago would find him much more appealing today. He moves about in a different world now, away from the spotlight.

“The limelight is there to enjoy when you’re in it,” he says. “And when you’re not in it anymore, enjoy wherever you are. I’m not a professional athlete anymore. I’m just a different person. I have great memories and some accomplishments, and I have moved on.”

Originally published 2/17/06 in the Portland Tribune(Reprinted with permission)(BruinBasketballReport.com)

(alumni tracker)(photo credit: AP)