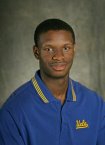

Richard Washington was a key member of John Wooden's last UCLA championship team in 1975 and the tournament MVP .

Richard Washington was a key member of John Wooden's last UCLA championship team in 1975 and the tournament MVP .

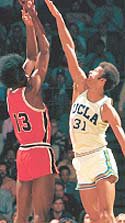

After his junior year at UCLA, Washington became the first Bruin to ever declare hardship and enter the NBA draft as an underclassman.Washington averaged 14.2 points and 6.7 rebounds per game at UCLA. He is No 31 on the all-time UCLA scoring list.SHOOTING STARBy Kerry Eggers

Writer, Portland Tribune

Originally published 12/9/05 in the Portland Tribune(Reprinted with permission)At 50, Richard Washington still looks like the athlete he was three decades ago at Benson High. Though he weighs maybe 65 more pounds than the 235 he carried during his six-year NBA career, the 6-11 former Tech star carries them well.

“I should work out more than I do,” says Washington, whose 1971 team was inducted last week into the Benson athletic Hall of Fame. “But my knees are bad. I can’t really run.”

Oh, how Washington could run in his days with Dick Gray’s Techmen — or, as they called them in those days, the Engineers.

An agile big man, Washington was a three-time all-state and first-team all-tournament selection. He led Benson to state championships in 1971 and 1973.

“Richard was athletic, and he could get up and down the court for a big guy,” says Leon McKenzie, the Benson track and field coach who played with Washington as a guard on the ’71 team.

“A finesse player,” says Gray, who lists Washington and A.C. Green as the best players he coached over a storied 38-year career. “Richard could pass, dribble and shoot, which is something not a lot of big men could do in those days.”

Washington had a stellar career at UCLA, earning first-team All-American honors as a junior in 1975-76. In his three seasons at Westwood, the Bruins went 26-4, 28-3 and 28-4, and won three Pac-8 championships, made three Final Fours and seized the NCAA title in 1975. That year, Washington was named most valuable player of the Final Four.

When he became the first UCLA player to declare hardship and enter the NBA draft early, taken by Kansas City as the third pick of the 1976 draft, the world seemed his oyster.

Six years later, at age 26, he was out of both the NBA and basketball for good.

Injuries played their part, but Washington acknowledges that a lack of desire had its role in his premature retirement from the game.

“I wasn’t real satisfied with my NBA career,” Washington says. “I spent most of my basketball life being kind of a naive person, not really knowing how seriously other people took it. In the pros, basketball stopped being fun for me.”

Washington moved to Milwaukie in 1982, shortly after his last NBA appearance with Cleveland. He and his wife, Leiko, have raised two daughters.

After his NBA career, “I was fairly sure I didn’t want to do anything in basketball,” he says. “I didn’t feel like I could keep competing without a love of the game. That’s what made me want to get out there and work out when there was nobody else around.”

Building a new careerWashington began working with a friend in the remodeling business. Twelve years ago, he founded Richard Washington Construction.

“One of the reasons I went to Benson was because when I was young, I was doing one of two things — playing basketball or at a construction site, watching workers build houses,” he says. “I’m a general contractor now, so I sub(contract) everything out. I enjoy it. Business is good. I’ve even gotten some jobs because I used to play basketball and people recognize my name.”

Who could forget Washington?

“In my mind, Richard is the greatest prep player ever in the state of Oregon,” says Craig Conway, a former teammate who now is a middle-school teacher in Springfield. “What was unique about Richard was he was quick, he could shoot, he had such a great touch, but he wanted to include everybody, too.

“He always had a great sense of humor. He didn’t take himself too seriously. He’d smile and keep us loosened up. I always appreciated his kindness, his personality, his respect for others and his unselfishness as a player. He didn’t want to draw attention to himself.”

That was hard to do. Washington was always the biggest kid in his class, and beginning in third grade at Boise Elementary in North Portland, basketball was his thing.

“At recess, you’d go check out the footballs at the noon hour,” he says. “I was always late, so I got stuck with the basketball. And I learned to love it. I was pretty good right off the bat.”

Boyhood pal George Mayes, later a starter on the great teams at Benson, recalls their formative years growing up on North Cook Street.

“We used to drag Richard out to play basketball with us,” Mayes recalls. “At first, his sister used to beat him up on the basketball court. But we started playing every day, and he started coming into his own about his freshman year. He had the quickness and agility and an inside-outside game.

“I wish he’d played more inside, but he had that outside shot.”

Almost a GeneralWashington nearly wound up at Grant.

“I wanted to go to Benson because it was an all-boys school,” he says. “I didn’t like girls at the time. But my original application got refused.”

Washington was scheduled to attend Grant. But he accompanied Mayes to a preseason Benson football practice before his freshman year, and coach Mike Lopez spied him.

“He took me down to the office, and then next thing I knew, I was going to Benson,” Washington says.

As a 6-5 freshman, Washington was a starter for Gray. By the time he was a 6-9 sophomore, he was a dominant player. If not for an upset by Sunset in the state quarterfinals his junior season, Tech might have won three straight state titles. Gray liked to run and gun, and Washington had the luxury of some outstanding teammates, such as Mayes, Rickey Lee, Gary Gray (the coach’s son) and Mark Hoisington.

“Dick was great to play for,” Washington says. “He made the game fun, which it should be for kids at that age. All of us can look back on it with a lot of fond memories. We all looked forward to basketball practice.

“There were a lot of good players in the PIL at that time, guys like Ray Leary, Charles Channel, Carl Bird, Tony Hopson, June Jones, Artie Wilson, Tim Stambaugh and Eddie Lincoln. It was a time when there was a lot of good basketball in the city.”

Gray noted a change in attitude in Washington midway through his high school career.

“It was great as a freshman and sophomore, but he was not quite as devoted the next couple of years,” Gray says. “He discovered females. He didn’t have quite the same desire, but we were winning by 20, 30 points most games, so he didn’t have to. I told him, ‘OK, you have to be ready for the big games,’ maybe four or five times each year. And he was.”

Washington was an all-around athlete, a hurdler in track and good enough as a defensive end-receiver to be the MVP on the Benson football squad his junior year before he hung up the cleats.

“At that point, everybody knew he was going to be a great hooper,” McKenzie says. “We kept hearing opponents say, ‘Let’s take his knees out.’ We thought it was better he step out away from football as a senior. He wasn’t going to play college football.”

Weather and John WoodenWashington could have played basketball at any college in the country. He chose UCLA and the legendary John Wooden.

“I wanted to get out of state, just for a change, to experience something new,” he says. “The other school I thought seriously about was Hawaii. I visited there as a sophomore and I loved the weather, the tropical feel of it. I ended up at UCLA because people said (the Bruins) could offer all the same things, but they also had John Wooden and the tradition.

“Funny, because I wasn’t really aware of UCLA’s legacy. I was not a great student of the game. I was a kid who lived for the moment.”

Washington, who played alongside senior Bill Walton as a freshman at UCLA, was a member of Wooden’s final two teams in Westwood.

Playing for Wooden “was kind of surreal,” Washington says. “I didn’t fully appreciate it until many years after. It was a good situation. There was so much talent there. Coach Wooden commanded so much respect, the players listened to every word he said. You see what can happen if you put all the right forces together.”

Washington got off to a nice start in the NBA, averaging 13.0 points and 8.5 rebounds as a rookie and 12.8 points and 8.4 boards the next season under Kansas City coach Phil Johnson.

“The one thing Richard could do immediately was offensive rebound,” says Johnson, now an assistant with the Utah Jazz. “That was his strong point. That’s what he helped us with when he first came.”

Things went downhill his third season. Washington broke his foot and played only 18 games.

“After that, Richard was never the same player,” says Billy McKinney, Washington’s teammate his third season with the Kings. “One of the things people always wondered about him was his toughness. Richard was always kind of a laid-back player. Sometimes people misread that as a lack of toughness.

“But he was such a skilled player. At 6-11, he could do so many things. The guys used to always ride him about that. Guys like Sam Lacey, a great team leader, got on him pretty good, but Richard didn’t respond to that too well. That’s probably why his career was short.

“He was an incredible talent. Some of the people around him were frustrated because they understood what he could do. He was a great guy, but he didn’t live up to everybody’s expectations.”

Says Johnson: “As a person, Richard was fine, but he didn’t work as hard as he probably should have. We knew he had talent; we just expected him to play harder.”

Washington was traded to Milwaukee, then to Dallas, then to Cleveland. Along the way, he injured both knees, which robbed him of his mobility and, ultimately, his desire to continue playing.

(BruinBasketballReport.com)

(alumni tracker)(photo credit: AP)

Box Score

Box Score