Ben Stellar

By Steve Springer, Times Staff Writer

Los Angeles Times

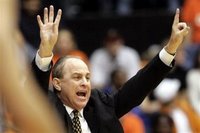

The Pac-10 champion Bruins have been focused under Howland, who is right on schedule in his third season in Westwood

The Pac-10 champion Bruins have been focused under Howland, who is right on schedule in his third season in WestwoodHe never saw a kid he didn't think he could successfully recruit, never saw a bad call he wouldn't ferociously dispute. He never saw an offense he didn't think he could frustrate, never saw a defense he didn't think he could dominate.

There is no room for doubt in UCLA basketball Coach Ben Howland's world. There are absolutes.

And losing focus is absolutely forbidden.

Early this season, the Bruins found themselves in trouble on a snowy day in Ann Arbor, Mich., falling behind the Wolverines, 8-0, in front of a pumped-up crowd in Crisler Arena. Then, UCLA guard Arron Afflalo hit the ignition switch on his team's offense, making four three-pointers and scoring 14 of the Bruins' first 16 points to get his team back into the game.

But then, while in his own frontcourt, Afflalo thought he was fouled but failed to get a whistle. As Michigan gained possession and the rest of the players raced to the other end of the court, Afflalo lagged behind to question a referee.

Even though the Bruins had regained the momentum, even though it was Afflalo's hot hand that had cooled the crowd, Howland called time out and got on Afflalo — in front of his teammates, the crowd and an audience viewing on national TV.

Mental discipline must be maintained and there are absolutely no exceptions.

"He is very intense," said UCLA assistant Ernie Zeigler, now in his third season under Howland at UCLA after working for him for two seasons at Pittsburgh. "Some people might look at it as brashness, but if you don't get the opportunity to know him, you don't understand how great a guy he is."

His players have bought into Howland's approach.

Afflalo certainly did that day in Ann Arbor.

"The coach got on me and he should have," Afflalo said. "He's not supposed to cater to me. This is not the NBA. He's supposed to harp on me when I deserve it."

Howland's methods are paying off this season. The Bruins begin play this afternoon in the Pacific 10 Conference tournament at Staples Center with a 24-6 record that includes a 14-4 mark in the conference, good enough to give UCLA its first conference title in nine seasons.

And for his success, Howland was chosen conference coach of the year. It's a pattern of success that Howland has woven through a coaching career that spans more than two decades.

After graduating from Cerritos High and playing for Santa Barbara City College and Weber State, then putting in 14 years as an assistant at Gonzaga and UC Santa Barbara, Howland got his first head coaching job at Northern Arizona in 1994. After going 9-17 and 7-19 his first two seasons, Howland led the Lumberjacks to a 21-7 mark in his third season, the 10th-best single-season turnaround in NCAA history.

For that, he was chosen Big Sky Conference coach of the year. The next season, he led Northern Arizona into the NCAA tournament for the first time in school history.

After five seasons at Flagstaff, Howland moved to Pittsburgh. The pattern was repeated. The Panthers went from 13-15 and 19-14 to 29-6 in Howland's third season. Pittsburgh got as far as the Sweet 16 in the NCAA tournament that season and Howland was chosen national coach of the year by the Associated Press. The next season was more of the same, the Panthers going 28-5 and again reaching the Sweet 16.

People back home in California noticed. On April 3, 2003, Howland became coach of the Bruins. UCLA was 11-17 and 18-11 the first two seasons under Howland. Once again, the third time was the charm.

The Bruins' success has been based on a foundation of solid defense. No surprise. It's telling that Howland was twice chosen Weber State's most valuable defensive player because defense has been his mantra throughout his coaching career.

"Winning starts with defense, whatever sport you are talking about," Howland said. "Michael Jordan was the greatest defensive player in NBA history at his position. The great Laker teams, whether under Phil Jackson or Pat Riley, started with defense. I loved guys like Michael Cooper and Dennis Johnson, who played great defense."

And Howland, 48, made it clear the first time he addressed his first UCLA squad, that they were going to be active at both ends of the court or inactive on the bench.

"If you are a negative defensively, that's going to limit your minutes," Howland said. "You have got to be able to go out there and hold your own and not hurt your team when playing defense, or not play at all."

Howland knows it can be a struggle to persuade kids weaned on "SportsCenter" dunks to pay attention to the guy trying to stop that dunk.

"As kids grow and learn more about the game," he said, "and want to get to the next level, the NBA, which they all do, they'd better be able to play both ends of the floor because all the great ones do. It's more fun to play offense than defense. But the most fun is to win."

It wasn't a hard sell to the Bruins, said Cedric Bozeman, a fifth-year senior.

"Coach talked about defense from day one," he said. "He talked about it as far as the left side of the won-loss column, the W side."

Howland has always stuck strictly to a man-to-man defense, although he now varies that a bit by double-teaming the player in the post.

"A good man-to-man is like a zone and that is a John R. Wooden quote," Howland said. "The NBA is allowed to play zone now, but no one is playing it because it is easier to score against a zone than against man-to-man if you are patient and have good players."

Howland says he gained inspiration from three fellow coaches: Jerry Tarkanian, Rick Majerus and Jerry Pimm.

It was under Pimm at UC Santa Barbara that Howland learned his craft and Pimm still chuckles at the length he had to go to keep his intense assistant under control.

"He would get upset over a call," Pimm said, "and I finally had to tell him, 'You sit and watch the substitutions and I'll take care of the officials.' But he would bark at them until he got it off his mind.

"It was tough for him to stop recruiting a guy even after we learned the player had already committed elsewhere. 'We can still get him, Coach,' he'd say. 'We can still get him.' He doesn't like to let go."

Howland also has trouble letting go after a loss.

"It's like a hole in his gut," Zeigler said. "He can't put that feeling away until he figures out why we lost. We may watch a tape of the game over and over for hours until we are mentally exhausted. He doesn't eat and has a difficult time sleeping after a loss."

Howland's intensity carries over to practices. Detailed stats are kept on every aspect. That means not only the usual — shots, rebounds, assists and steals in scrimmages — but also charges, deflections, post feeds, screens and the number of times contact is made on screens.

And Howland processes it all in making personnel decisions.

"He's big on numbers," said assistant Chris Carlson, who has been with Howland since the Northern Arizona days. "And he's got a photographic memory. He can tell you the starting lineup of a game between Santa Barbara and Long Beach back in 1991 and what the score was with a minute and a half to go."

Howland is also big on the numbers appearing on his watch. He is meticulous about adhering to a schedule, whether it be when his players eat, the bus leaves for the arena, the players dress for the game and they start their pregame warmup. Howland appreciates tardiness about as much as he appreciates lazy defense.

"He got that from me," Pimm said. "If you are going to be late to practice, you are going to be late getting back on defense."

His intensity can get Howland in trouble. He will call a timeout whenever he has a message for his team or wants to send a message to the other team, sometimes leaving him without a timeout when it is needed in the closing minute of play.

There are few diversions in Howland's life. He doesn't play golf, doesn't play tennis.

"Basketball has been his life," Pimm said. "It's not a job to him."

Other than the time he spends with his family, including wife Kim and their two grown children, Howland's only hobby is fly fishing, if he can sneak in a few weeks in the off-season.

So then, he finally cuts back on the intensity and just enjoys the lazy atmosphere?

Uh, no.

"I'm there," he said, "to catch fish."

Orginally published in the Los Angeles Times March 9, 2006

(reprinted with permission)

(BruinBasketballReport.com)

(photo credit: AP)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Back To Bruin Basketball Report Home